Thickeners Overview

What can you do by simply changing the texture of a liquid? The flavor stays the same, doesn't it? And the addition of thickening agents provides little nutritional value. So why do so many modernist chefs choose to use thickeners?

By many measures, thickeners have been the most important innovation in molecular gastronomy. Certainly, thickeners account for the largest proportion of new modernist ingredients employed by chefs.

Collectively, these ingredients are known as "hydrocolloids." The term "hydrocolloid" covers a wide range of materials. Technically, a hydrocolloid is any molecule that can be evenly dispersed through water. We generally mean the term to describe ingredients that have either a thickening or gelling effect. The difference between a thickened liquid and a gel? A gel can display the characteristics of a solid, while a thickened liquid always behaves as a liquid.

How do thickeners work?

Before discussing modern thickeners, let's take a quick look at how non-hydrocolloid thickeners work.

Consider a blended pesto. Many pestos are thickened by adding nuts to the mix. When the nuts are blended, they add small chunks of mass, evenly distributed throughout the pesto. The mass of the nuts are what give the pesto thickness. The thickness of the pesto can never surpass the thickness of the nuts themselves: if you were to blend the pesto even more, it would become thinner, not thicker.

Nuts are thickeners, but they are not hydrocolloids. Hydrocolloids have physical properties that allow them to thicken liquids far more than through mass alone.

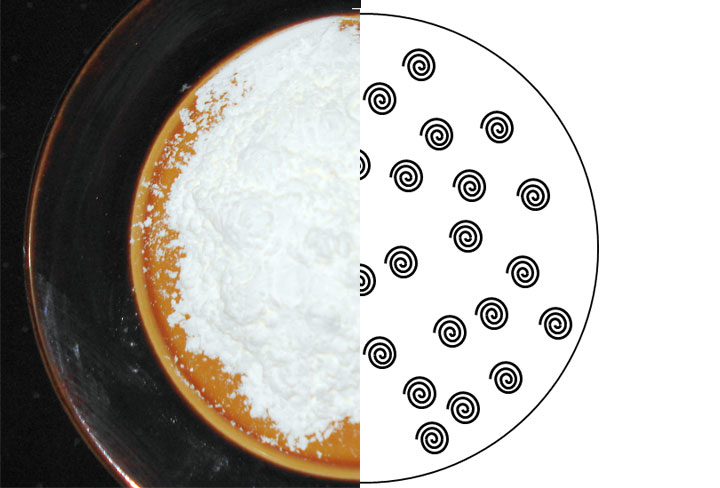

Let's look at cornstarch, a common kitchen hydrocolloid, as an example.

When you buy a canister of cornstarch, it arrives in powdered form. The powder is very little body or thickness. At a microscopic level, what's happening is that the starch molecules from the corn are tightly wound together and dehydrated. Each packet of starch, represented below as spirals, stands alone and does not attach itself to any other packet of starch.

When you add cold water to cornstarch, the starch molecules evenly disperse into the water. In cooking, this is called a slurry. The packets of starch are still in their tight spirals, but now they are evenly spread into water.

[image: Rebecca Siegel]

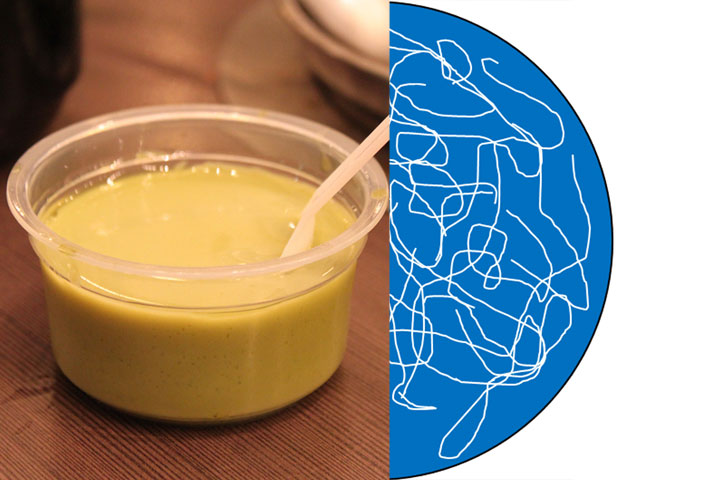

When you heat cornstarch that has been dispersed in water, the heat and water act together to hydrate the cornstarch molecules. The tightly-wound spirals of starch unwind and begin to give a little thickness.

[image: maya83]

In the case of cornstarch, the starch molecules hold more and more tightly on to one another as the temperature of the mixture decreases. That's why cornstarch can create a tempting pudding at refrigerator temperatures, but why it's better suited for use as a sauce thickener at higher temperatures. Conversely, it's the same reason why hot and sour soup thickened with cornstarch turns into a globular mass when stored in the refrigerator.