Umami – The Delicious 5th Taste You Need to Master!

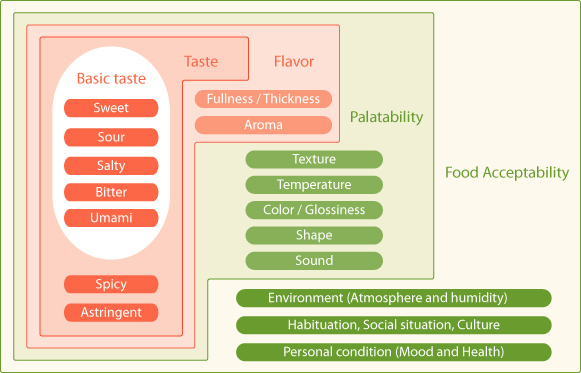

Though this may seem to be the latest buzzword in the culinary field, the umami taste has been around literally forever. It’s actually one of the five basic tastes, as are sweet, sour, salty and bitter. The umami taste is savory and is most often associated with meats such as cured ham, seafood including anchovies and dried bonito as well as tomatoes, mushrooms, and some cheeses. Would you know it if you tasted it, or would you just think that the dish had that “extra something”? By the end of this article, you’re going to know all about umami so read on!

Literally translated, the Japanese word umami means “delicious taste” or “pleasant savory taste” and was coined by Professor Kikunae Ikeda in 1908 when he discovered that monosodium glutamate, naturally present in some foods, reacts synergistically with some ribonucleotides, including

inosinate and guanylate. That sounds really scientific but what it basically means is that chemicals in some foods interact in a special way to really impress your taste buds.

Umami has a mild but lasting aftertaste difficult to describe. If a flavor had to be assigned to the term umami, it would be meaty and brothy with a tongue-coating savoriness that causes salivation.

If you want to truly elevate the flavors of your dishes, you need to understand the science behind umami. But don’t worry, we’ve got you covered! We’ll explain you the science, list the naturally rich umami foods you should know about and discuss how some of the top chefs in the world are incorporating umami to their signature dishes.

Dr. Ole Mourtisen, from Center for Biomembrane Physics at the University of Southern Denmark, recently presented “Deliciousness and the Science Behind It” at an Experimental Cuisine Collective meeting. Dr. Mourtisen has written several papers about umami with very interesting findings that we’ll cover here.

The Discovery of Umami

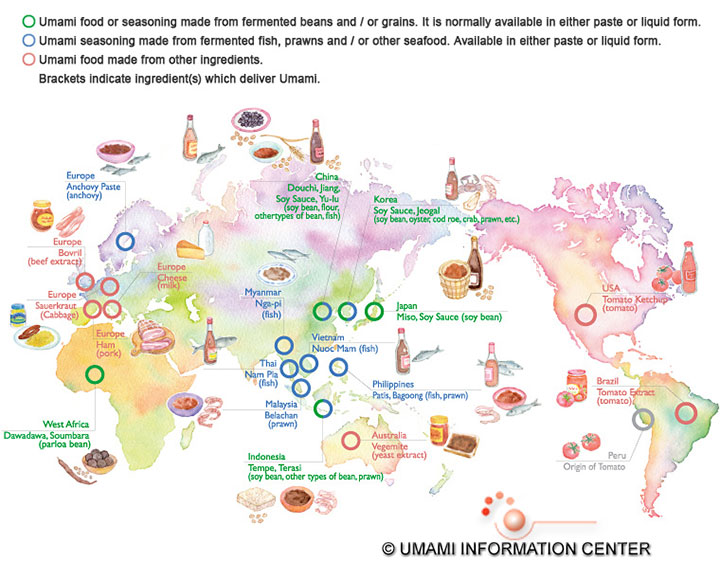

Umami has been recognized as an independent flavor for more than a hundred years in several different cultures. The Romans have actually cooked with glutamate for centuries as have the Japanese but it was just another undefined flavor to add to dishes.

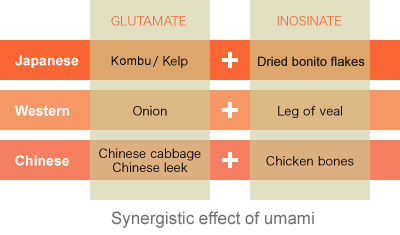

As we’ve already discussed, the actual attempts to define umami started in 1908 when Professor Kikunae discovered that monosodium glutamate (MSG) was one of the main flavor components in dashi, a delicious aqueous Japanese broth that’s used similarly in Japanese cuisine to the way that Westerners use beef stock or bouillon. The glutamate he found in dashi came from kombu, a large brown seaweed used to make dashi.

As we’ve already discussed, the actual attempts to define umami started in 1908 when Professor Kikunae discovered that monosodium glutamate (MSG) was one of the main flavor components in dashi, a delicious aqueous Japanese broth that’s used similarly in Japanese cuisine to the way that Westerners use beef stock or bouillon. The glutamate he found in dashi came from kombu, a large brown seaweed used to make dashi.

The other key component in dashi is katsuobushi, dried bonito fish. In 1913, much to the surprise of many, Shintaro Kodama found that it was the inosinate released from the katsoubushi that elevated the umami taste in dashi. In 1957, Akira Kininaka completed the initial round of umami discoveries when he figured out that guarylate, a compound found in dried shiitake mushrooms, was also an umami flavor contributor. Dried shiitake mushrooms are usually used instead of katsoubushi in vegetarian versions of dashi.

People began to suspect that these three components interacted with each other in a way that really elevates the umami flavor in many foods such as dashi. The key, then, is to find ingredients that have high amounts of glutamate and either of the nucleotides such as is found in sun-dried tomatoes or dried mushrooms.

People began to suspect that these three components interacted with each other in a way that really elevates the umami flavor in many foods such as dashi. The key, then, is to find ingredients that have high amounts of glutamate and either of the nucleotides such as is found in sun-dried tomatoes or dried mushrooms.

The final nail that secured umami as a 5th basic taste right up there with sweet, salty, bitter and sour was the discovery in year 2000 of an actual umami taste receptor in human taste buds that was dubbed taste-mGluR4. It was now officially scientifically proven and umami was formally recognized as an independent basic flavor.

By itself, the taste of pure MSG is not necessarily pleasant and it has been described as salty, soapy and broth-like. But it makes a great variety of foods pleasant especially in the presence of a matching aroma within a relatively narrow concentration range. MSG in excess amounts makes the food less palatable and an optimum amount appears to be around the concentration found in many natural foods, typically 0.1–0.8% by weight.

Umami Isn’t Just Another Taste

One of the reasons that umami was designated as an independent flavor is because the MSG and the ribonucleotides combine to make a flavor that either ingredient alone simply doesn’t contribute. It’s this elevation in taste that leads to such pairings as the bonito and kombu seaweed in dashi.

In addition to rounding out the flavors of dishes such as dashi where it’s the predominant flavor, umami also elevates some of the other basic flavors, sweet and salty in particular. For example, when paired with salty flavors, the saltiness is elevated to the point that you can actually use up to 40% less salt than you typically would without negatively impacting the taste of the dish.

Umami does the same thing for fatty flavors. For instance, just a little bit of dashi added to clam chowder or other soups infuses a slightly smoky flavor reminiscent of bacon without actually using the fatty ingredient.

If you’d like to consciously use umami in order to decrease sodium levels in your fish or meat dishes, using dashi or veal stock are excellent options. Another great umami flavor combination that nearly everybody recognizes is sun dried tomatoes, dried shiitake mushrooms and parmesan cheese, as are found in many different Italian dishes. Remember that if an umami recipe calls for fermented, dried, or sundried ingredients, it’s important to use those versions instead of the fresh in order to obtain the ultimate umami profile.

Foods That Contain Large Amounts of Natural Umami

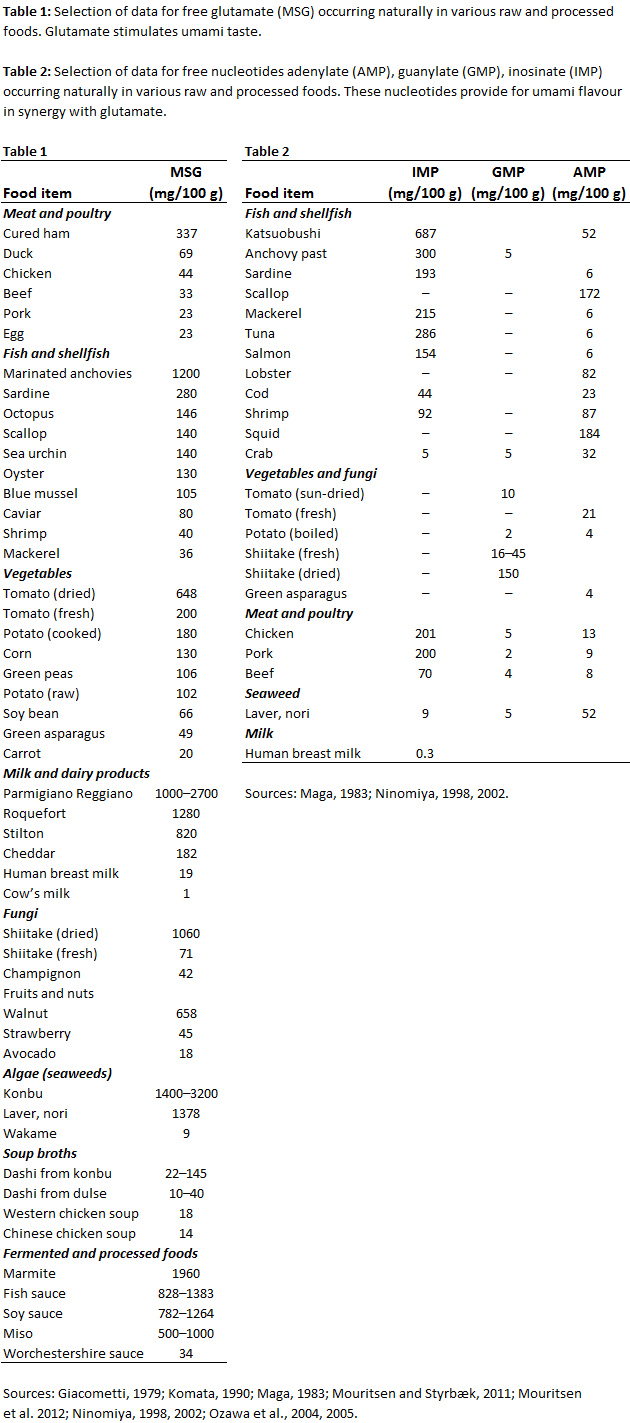

Some foods are naturally rich in both glutamate and one of the ribonucleotides and thus deliver a rich, deep umami taste, especially when paired with other umami foods. Glutamate is found in many different foods including meats, seafood and many vegetables. Guanylate is more often found in vegetables and inosinate, if present, will generally be found in meats.

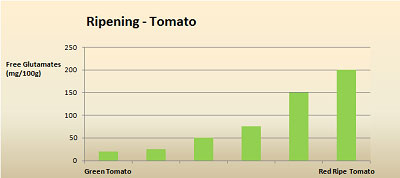

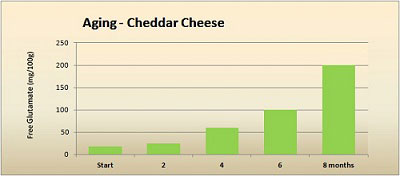

Most raw meats and vegetables contain high levels of glutamic acid (glutamate in acid form) but it is bound in proteins. Glutamic acid imparts little umami taste; whereas the salts of glutamic acid, known as glutamates, can easily ionize and give the characteristic umami taste. Therefore, the bounded glutamic acid found in many common foods needs to be released to produce umami taste. To provide umami, most raw foods need to be processed to break down the proteins into free amino acids and the nucleic acids into free nucleotides.

Most raw meats and vegetables contain high levels of glutamic acid (glutamate in acid form) but it is bound in proteins. Glutamic acid imparts little umami taste; whereas the salts of glutamic acid, known as glutamates, can easily ionize and give the characteristic umami taste. Therefore, the bounded glutamic acid found in many common foods needs to be released to produce umami taste. To provide umami, most raw foods need to be processed to break down the proteins into free amino acids and the nucleic acids into free nucleotides.

Processes such as cooking, boiling, steaming, simmering, roasting, braising, broiling, smoking, drying, maturing, marinating, salting, ageing and fermenting all contribute to the degrading of the cells and the macromolecules of which the foodstuff is made. Of these processes, fermenting, by microbes such as yeast and bacteria or by enzymes, is by far the most potent method of freeing umami compounds. That's one of the reasons why fermentation has become a hot topic for scientists and chefs including Chef Rene Redzepi at his Nordic Food Lab and the momofuku team, led by Chef David Chang.

Processes such as cooking, boiling, steaming, simmering, roasting, braising, broiling, smoking, drying, maturing, marinating, salting, ageing and fermenting all contribute to the degrading of the cells and the macromolecules of which the foodstuff is made. Of these processes, fermenting, by microbes such as yeast and bacteria or by enzymes, is by far the most potent method of freeing umami compounds. That's one of the reasons why fermentation has become a hot topic for scientists and chefs including Chef Rene Redzepi at his Nordic Food Lab and the momofuku team, led by Chef David Chang.

These are some foods that are naturally rich in umami flavor that you should know about.

- Tomatoes – though fresh, ripe tomatoes contain plenty of glutamate, sun-drying them really elevates the umami flavor. As the chart above shows, ripening increases the content of glutamate.

- Shiitake mushrooms – as with tomatoes, drying shiitakes doubles their levels of glutamate per gram.

- Many cheeses – hard cheeses such as parmesan and bleu that have undergone all of the phases of aging are particularly rich in umami flavor. As shown in the chart above, the content of glutamate of cheddar cheese increases significantly with aging.

- Soy beans – used by the Japanese for centuries in many different ways, soy beans are the basis for soy sauce, tofu and miso paste just to name a few. Fermented soy is even higher in umami.

- Dry-Cured Hams such as prosciutto because during the drying process the protein in the meat is degraded, releasing enzymes and elevating the umami essence.

- Fish sauces or stocks made from such fish as bonito, tuna, anchovies or niboshi after they have been dried.

- Fresh fish such as sea brim, mackerel, tuna and cod are all rich in glutamate.

- Seafood, including shrimp, scallops, squid, clams and mussels all lend excellent umami flavor.

- Seaweed and sea vegetables such as kombu, nori and wakame are particularly high in umami when dried.

- Potatoes have a high glutamate level and when stored for a long time at temperatures just above freezing, they taste sweeter.

- Cabbages such as hakusai are excellent umami additions to stir-fries, soups and stews. They’re also great as side dishes or to use as garnishes, especially when fermented. They pair extremely well with seafood (as seen with the Korean dish kimchi) to create a robust umami flavor.

- Two spirits that are rich in umami are Sake and Shochu.

Below are two tables with the amounts of glutamate and nucleotides occurring naturally in raw and process foods. Keep these in mind when creating your next signature dish and bring out the umami flavor!

Bring Out the Umami with Dashi!

The simple Japanese fish stock, dashi, is being used by some of the top chefs on the planet regardless of their style of cuisine because it’s an invisible component that enhances the umami of a dish without adding fishy flavor.

La Bernardin Chef Eric Ripert uses dashi to bring a greater depth to many of his dishes such as Kumamoto oysters with dashi gelée, to finish mushrooms and to brush raw fish before layering on olive oil and citrus.

At Per Se, Chef Jonathan Benno, incorporates dashi into preparations of Japanese fish, like a grilled hamachi belly canapé with dashi poured tableside.

Chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten uses dashi to accentuate the flavors of his grilled foie gras, snapper and caramelized sirloin and to add umami flavor to a light mayonnaise.

Chef David Kinch at Manresa, in Los Gatos, Calif., applies dashi as a seasoning or uses it as a versatile blank slate, delicately infusing soups and vegetable dishes. “It imparts that savoriness in anything it touches,” he said, “even in small, negligible amounts.”

Laurent Gras of L2O in Chicago, who makes his dashi with the aid of a high-tech Gastrovac vacuum cooker, transforms a chicken bouillon into intense chicken dashi bouillon. “You can take chicken and bring it to a meat level” of taste, he explained.

Dashi’s smoky nose is what appeals to Gabriel Bremer, the chef at Salts, in Cambridge, Mass. He suffuses a light cream sauce with dashi to subtly mimic the smokiness of bacon, applying the emulsion in a deconstructed New England fish chowder.

At Cyrus, in Healdsburg, Calif., Douglas Keane prepares a broth of dashi and citrus (sudachi) to serve as an “umami canapé,” balancing the savoriness with the acid. “Your palate actually wakes up and goes, man, that’s good,” he said.

Linton Hopkins of Restaurant Eugene in Atlanta contrasts the stock’s lightness with rich French butter to glaze root vegetables, sharpening and coating the ingredients at the same time.

The Nordic Food Lab, a non-profit created by Chef Rene Redzepi of Noma, has been using a local seaweed called dulse to make a Nordic version of umami rich dashi. They have also experimented using dulse to make ice cream, fresh cheese and bread with umami taste by infusing milk with the seaweed or using dulse dashi.

Check out the recipe to make the classic dashi at the end of this article and start experimenting to create your own dishes rich in umami flavor.

Incorporating Umami in Your Dishes with Other Ingredients

Dashi is the classic example of pure umami flavor and is a great simple way of adding the 5th flavor of deliciousness to a wide variety of dishes thanks to its neutrality. However, as we have explained before, there are plenty of ingredients rich in umami flavor that could be used instead of dashi.

Let’s look at Peruvian food for example. Ceviche is rich in umami flavor thanks to the denaturalization of raw fish when mixed with lemon and salt. "Chicha de jora", a beverage obtained from corn fermentation, is frequently used in Peruvian dishes to bring out the umami flavor. Another typical ingredient used to create deliciousness is a caramelized paste of garlic, chili and onion that is the base of Peruvian cooking.

Chef Yoshihiro Takahashi marinates beef with sake and sun-dried tomatoes which, like kombu, contain high levels of glutamate that in combination with the inosinate in the meat, produce a strong umami flavor.

Some flavors are already “in your face” umami but some, such as that of chicken, require the addition of other umami foods in order to truly bring out the natural flavor. Leeks and mushrooms both pair well with chicken to enhance the 5th flavor.

Chef Yasuhiro Sasashima puts in some kombu when boiling pasta to get delicious pasta in which the umami and the saltiness are brought out nicely. Instead of making stock from kombu and katsuobushi, he uses cured Italian ham which contains the same umami parts as katsuobushi.

The stock used in Chinese cooking, tan, has many varieties compared to the dashi used in Japanese cooking. However, its intense umami flavor does not come from the dried bonito fish, but from other ingredients. In one variety, shantan, the umami comes from jin hua huo tui - pork leg meat, which has been cured for two and a half years. Other tans get the umami flavor from dried shark's fin, dried abalone, dried shiitake mushrooms, dried scallops and dried shrimps which have been aged for a long time to develop the umami flavor.

Understand the Science and Create Deliciousness

The main point is that if you’d like to truly elevate the flavors of your dishes, then you need to pay special attention to the science of food. This is how the most brilliant chefs become the bests in the world – they know what their foods taste like and they know why they taste that way. Just like with any successful experiment, you have to know what’s going on chemically with the ingredients before you can truly exploit the potential. That’s truly the secret to making a dish more delicious than the sum of its parts!

Dashi Recipe

Dashi is very simple to make and has pure umami flavor that can be used to enhance a wide variety of dishes.

Makes 3 cups

-4 cm x 4cm dried kombu (kelp)

-3 cups (600ml) water

-8 g bonito flakes

Make a few slits in the kombu and cook it in the water on a medium heat. Remove the kombu just before it boils and add the bonito flakes. Bring to the boil and strain.

Sources

Molecular mechanism of the allosteric enhancement of the umami taste sensation, Ole G. Mouritsen and Himanshu Khandelia

Umami flavor as a means of regulating food intake and improving nutrition and health, Ole G Mouritsen Abstract

Umami Information Center

The Secret’s Out as Japanese Stock Gains Fans – The New York Times

(8 votes, average: 4.50)

(8 votes, average: 4.50)