Sous Vide Cooking: An Introduction

by Douglas E. Baldwin

Sous vide is French for “under vacuum” and describes the cooking of raw ingredients in heat-stable, vacuumized pouches at precise temperatures. Despite its name, precise temperature control is more important for chefs than vacuumized packaging. Sous vide cooking has been used in the world’s top restaurants since the 1970s, was extensively studied by food scientists in the 1990s, and started showing up in home kitchens in the late-2000s.

Precise temperature control has several benefits: it allows almost-perfect reproducibility; it gives greater control over doneness than traditional cooking methods; the food can be pasteurized and made safe at lower temperatures — so it  doesn’t have to be cooked well-done to be safe; and tough cuts of meat can be made tender and still be a medium or a medium-rare doneness. Vacuum-sealing allows for efficient heat transfer from the water (or steam) to the food, it increases shelf-life by eliminating the risk of recontamination during storage, it helps inhibit off-flavors from oxidation, and it prevents evaporative losses of flavor volatiles and moisture during cooking.

doesn’t have to be cooked well-done to be safe; and tough cuts of meat can be made tender and still be a medium or a medium-rare doneness. Vacuum-sealing allows for efficient heat transfer from the water (or steam) to the food, it increases shelf-life by eliminating the risk of recontamination during storage, it helps inhibit off-flavors from oxidation, and it prevents evaporative losses of flavor volatiles and moisture during cooking.

Basic Techniques

Sous vide cooking has three basic steps:

- You prepare and then vacuum seal (small) portions.

- You heat the food with precise temperature control. Then you hold it until it has the texture you want or any foodborne pathogens have been reduced to a safe-level.

- (Optional) If you cooked it days (or weeks) before you need it, then you can rapidly chill the unopened pouch and refrigerate (or freeze) it until you need it. When you want to serve the food, you just reheat or rethermalize the food in a water bath at or below the temperature that it was cooked at.

- Finally, you remove the food from its pouch, sear or sauce if desired, and serve immediately.

Some foods benefit from sous vide cooking more than others. Meat, fish, and poultry are especially good. Vegetables, fruits, beans, and grains benefit less but can be delicious. Tender meat, fish, and poultry just need to get up to temperature and then, if desired, held at that temperature until any foodborne pathogens have been reduced to a safe-level. Tough meats, poultry, and plants are brought up to temperature and then held at that temperature until they’ve reached your desired tenderness. Tough meats are also sometimes brined, marinated, or mechanically tenderized before vacuum-sealing to improve texture and moistness — this is usually only necessary when cooking them well-done.

Vacuum sealing

To prepare the food for vacuum sealing, it’s generally recommended that you cut the raw ingredients into one to three serving portions since this will drastically reduce the heating time — this is essential when cooking fish and very tender cuts that'll become mushy or pappy if held too long. Tough cuts (of intact muscle) can be left in larger portions since they benefit from longer cooking times (and the interior of intact muscle meat is generally considered sterile). See Table 2.2 of my guide for heating times.

I usually cook meat and poultry without anything else in the pouch. I do this because it allows greater flexibility when preparing a large batch — say a dozen individually wrapped chicken breasts — in which most the portions will be refrigerated or frozen until they’re needed. Even salting a steak before cooking sous vide is only recommended when it’ll be served immediately (see this post at Cooking Issues). If what you're cooking will be served immediately, then you may want to add seasoning or a sauce before vacuum sealing.

Cooking

The temperature and time that you cook your food at depends on the food, the texture that you desire, and if you’ll be serving anyone who’s immune compromised.

Fish and tender cuts usually just need to be brought up to temperature and then served. If fish and tender cuts are held too long, they can become mushy or pappy because enzymes break down too much of the connective tissue and inter-fiber adhesion. This frequently means that fish and tender cuts cannot be pasteurized — that is, reduce any foodborne pathogens to a safe-level — and made safe for immuno-compromised people. Some tender cuts, such as poultry, should always be pasteurized since they’re likely to make even healthy people sick; see Table 4.1 of my guide for pasteurization times for poultry.

Tough cuts can be made tender and still be a medium-rare to medium doneness by converting collagen (the connective tissue that holds muscle fibers, bones, and fat in place) into tender gelatin by holding the meat at between 130°F/55°C and 140°F/60°C for six hours to three days. At below 140°F/60°C, enzymes (such as collagenases) can significantly increase tenderness after about six hours. Above about 130°F/55°C, heat will begin breaking down collagen into gelatin and reduce inter-fiber adhesion; the amount of time needed to tenderize decreases exponentially as the temperature increases, so it’ll take about 2 days to make a chuck roast fork-tender at 130°F/55°C and less than an hour in a pressure cooker. For more information, see §2 of my guide or my review article.

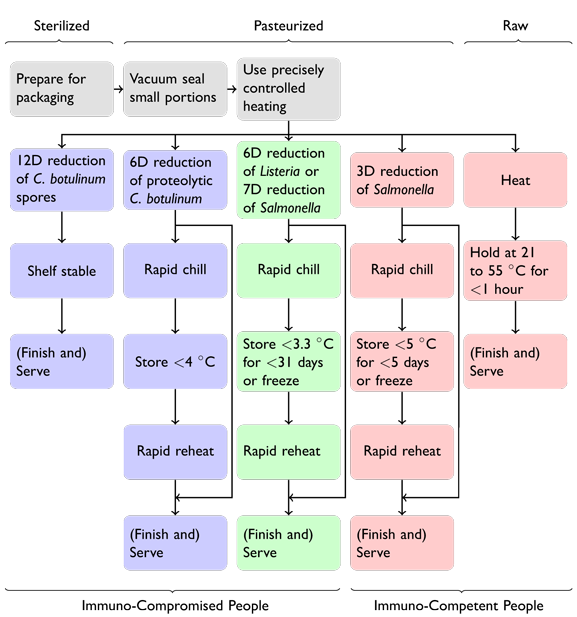

If you’ll be serving someone who is immune compromised, then it’s important to pasteurize the food by heating the food to above 126.1°F/52.3°C and holding it there until any foodborne pathogens have been reduced to a safe-level — see §1 of my guide for detailed information. Like the reduction of collagen into gelatin, the time required to reduction foodborne pathogens to a safe-level decreases exponentially with temperature. The amount a pathogen has been reduced is measured in decimal reductions, so a 6D reduction of Listeria monocytogenes has reduced the number of L. monocytogenes by 1,000,000:1. See the flow chart below of the various types of sous vide cooking based on the the severity of heating.

Finishing and Serving

Food that’s been cooked sous vide has the appearance of being poached; so fish, shellfish, eggs, and skinless poultry can be served as is; meat typically isn’t poached and is usually seared after cooking for both appearance and flavor. Searing or browning adds a lot of flavor because browning the lean tissues provides the savory and roast flavors of meat (while the species characteristics mainly come from the fatty tissues). Usually, you want to sear the outside (of food cooked sous vide) as fast as possible in order to prevent the interior from becoming overcooked and this suggests using a smoking hot pan or a blowtorch; see my guide for more information.

Sous Vide Equipment

Water Baths

There are several types of water baths on the market for both home and restaurant kitchens. The SousVide Supreme and SousVide Supreme Demi are great options for home cooks (especially the package sold at Costco.com). For home and professional cooks who need to heat larger quantities of food, the FreshMealsMagic and SousVideMagic combo from Fresh Meals Solutions is a great option. For professional cooks with a larger budget, the immersion circulators from PolyScience are excellent. I've used all three of the above systems and have no trouble recommending them; note that while I've interacted with the owners of all three companies, I don't get any compensation for recommending their products.

There are several types of water baths on the market for both home and restaurant kitchens. The SousVide Supreme and SousVide Supreme Demi are great options for home cooks (especially the package sold at Costco.com). For home and professional cooks who need to heat larger quantities of food, the FreshMealsMagic and SousVideMagic combo from Fresh Meals Solutions is a great option. For professional cooks with a larger budget, the immersion circulators from PolyScience are excellent. I've used all three of the above systems and have no trouble recommending them; note that while I've interacted with the owners of all three companies, I don't get any compensation for recommending their products.

Vacuum Sealers

For busy restaurant kitchens, frequently it’s easiest to fill the bath with stock or fat and cook the raw food in the bath without vacuum sealing. For home and smaller restaurant kitchens, the hassle of vacuum-sealing is made up for by less cleanup and the ability to refrigerate (or freeze) unopened portions.

For busy restaurant kitchens, frequently it’s easiest to fill the bath with stock or fat and cook the raw food in the bath without vacuum sealing. For home and smaller restaurant kitchens, the hassle of vacuum-sealing is made up for by less cleanup and the ability to refrigerate (or freeze) unopened portions.

For most home and restaurant cooks, Ziploc heavy-duty freezer bags work very well when cooking at below 195°F/90°C using my water-displacement method; see my guide. Most home cooks use clamp-style vacuum sealers, such as a FoodSaver, and these work well for recipes with little or no liquid in the pouch. Many restaurants use chamber-style vacuum sealers but pulling too strong of a vacuum can affect the texture of meat and fish (see this post at Cooking Issues).

Sous Vide Additional Reading

Web

- Douglas E. Baldwin, A Practical Guide to Sous Vide Cooking, 2008.

- Dave Arnold and Nils Norén, Sous-Vide and Low-Temperature Primer Part 1 and Part 2. Cooking Issues: The French Culinary Institute's Tecn'N Stuff Blog, 2010.

- eGullet's Sous Vide Index of the 2004–2010 topic “Sous Vide: Recipes, Techniques, & Equipment,” 2011.

Books

- Douglas E. Baldwin, Sous Vide for the Home Cook. Paradox Press, 2010.

- Nathan Myhrvold, Chris Young, and Maxime Bilet. Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking. The Cooking Lab, 2011.

- Thomas Keller, Jonathan Benno, Corey Lee, and Sebastien Rouxel. Under Pressure: Cooking Sous Vide. Artisan, 2008.

©2012 Douglas E. Baldwin